California Public Bank Charter

Scale of policy change (local, state, national): State

WHO – California Public Banking Alliance, a coalition of public banking activists working towards creating socially and environmentally responsible municipal and regional banks.

WHAT – AB 857, creating a state-level public bank charter for which local jurisdictions (e.g. cities, counties) in California may apply. A public bank is a bank that is owned, operated, and governed by a city or county in a given place.

WHERE – Across the state of California

WHEN – AB 857 was signed into law on Wednesday, October 2, 2019. It went into effect January 2020. Members of the California Public Banking Alliance have been organizing for the last few years in their various locales and came together for the first time in 2018 to work towards the state law.

WHY – To generate more resources and opportunities for public investment; to provide accessible and fair banking services (including access to capital) via a public option, which, ideally, meet the needs of communities where other financial institutions fall short. Public banks provide local governments an alternative place to hold public funds, like taxpayer money, outside of private Wall Street banks that do not serve public interests. Public banks end the extraction of public money (via fees) to Wall Street, and align public funds with the public’s values.

Interviewed: Sushil Jacob, senior staff attorney for economic justice at the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights of the San Francisco Bay Area. Member of the California Public Banking Alliance.

What’s the policy + why?

The policy, AB 857, creates a charter for public banks at the state level with California’s financial services regulator, the Department of Business Oversight. The purpose of the charter is to allow cities, counties, and regions of California to apply for a public banking license and form their own not-for-profit community development banks.

The idea behind the policy is to use the power of municipalities to create these public banking structures. They are called public banks because they are owned by public agencies, not private investors, and they hold public taxpayer deposits, rather than being private consumer banks – places where people hold their individual money.

“Municipalities are keystones to regional economies. They are crucial to the ability to organize and claim democratic power over and with public actors and institutions. It is in our cities and towns that we can really understand and actually meet the needs of people locally. We have to build from there first. It is important that yes, the bill was at the state level, but the state is not forming the bank. Working at the state level supported the purpose of empowering many cities and counties at once to form the banks. This is critical – we don’t just want one, we want many. We want a movement. We did this work in coalition and plan to continue it in coalition.”

Follow this link to see the original legislative proposal draft of AB 857 and this link to see the final legislation as it was passed into law.

Although the bulk of the bill stayed true to the original draft, key restrictions were placed on public banks as the bill went through committees in the legislature. Specifically, rigid prohibitions restrict public banks from most consumer or retail banking (i.e. personal/individual accounts and services).

Instead, these banks are likely to start out using partnership banking, i.e. making loans in partnership with local banks and credit unions. Cities and counties have seven years to apply and only ten licenses will be issued in the entire state. For now, organizers and advocates think ten licenses will be plenty of work, but they intend to push to have that number increased in the future. Meanwhile, organizers view this opportunity as a trial period.

Important amendments to the original draft include:

- Public banks are to be registered as nonprofit corporations (not for-profit shareholder corporations)

- They are required to carry FDIC insurance

- They are required to comply with collateralization requirements for public deposits

- They are severely restricted in their retail activities

- Voter referendum will be required for non-charter cities

Who decides?

California State Legislature.

What is the problem the community is working to address?

California does not have any deposit-taking public banks. All of the taxpayer dollars for all of the cities and counties, which are spent on programs for the benefit of the people, are held in private institutions, mostly Wall Street banks. None of that public money sits in public places. With the rise of Occupy Wall Street and Move Your Money campaigns, many people were alerted to the importance and opportunity to move their money out of Wall Street banks and into community banks.

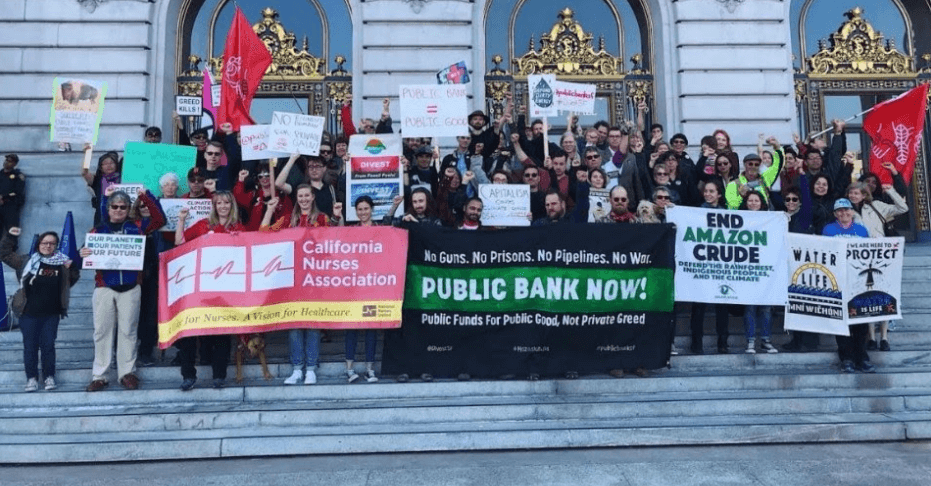

The public bank concept has existed for a long time, often in academic (rather than organizing) spaces. The Bank of North Dakota is a century old public bank and provides a model for the rest of the country. Recently though, the public bank movement gained immense momentum building on the enthusiasm and progress of divest/invest movements, particularly Indigenous-led efforts. The Financial Crash (and subsequent recession), Occupy Movement, and the rise of the Standing Rock #NoDAPL movement increased public scrutiny of the violent, unfair, and predatory practices of Wall Street banks. In particular, banks faced criticism — and in many places, broke the law — for shady activities such as sub-prime lending that disproportionately impacted (and has major lasting effects on) Black and Latinx homeowners. People like those at Standing Rock who were defending their rights to water and land, fighting against these banks’ funding of pipelines, began to push cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles to divest their public monies from these banks.

As activists across California started to agitate their cities to divest from Wall Street, they soon realized there were often no viable bank alternatives for cities. (For instance, Oakland broke off its relationship with Chase Bank, and moved to Union Bank, which is owned by a giant Japanese conglomerate.) Small local banks are not equipped to handle the scale of the banking needs of counties and cities. In order to manage a city’s money, for example, these local banks and their operating systems must comply with stricter rules, have a higher degree of protection, be able to provide collateral and more. These barriers constrain how much money in public deposits local banks can receive or will want to receive. So, taxpayer money is not usually going into local credit unions or community development banks, and instead is going to Wall Street.

Studying the Bank of North Dakota, members of the California Public Banking Alliance then began to put together legislation to demonstrate what it might look like for cities and counties to create their own banks.

In addition to the active harms that these Wall Street banks are causing, they also have little obligation (predominantly mandated through the Community Reinvestment Act) to serve people whose money they hold. This results in little public investment toward supporting local communities. Communities are looking for banks that would actually care about and want to support the needs of local people.

Who is organizing? How are people organized?

The California Public Banking Alliance is comprised of people representing different chapters organizing in their local communities for public banks across the state. The Alliance met in San Francisco in June 2018, with the first meeting convened by the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights. The Alliance created a strategy for a state-wide law that would enable all the local chapters to move forward with their respective public banks. The meeting was well-attended with members coming from Los Angeles, San Diego, Palo Alto and San Jose, the East Bay, San Francisco, Santa Rosa, Eureka, and Humboldt.

Groups working in all of these areas of California coordinate together through the Alliance, which developed sub-committees (legislation, political outreach, communications, etc) to organize the work. To pass the bill, they contacted all the allied legislators and organizations across the state, ultimately attracting over 180 endorsements from civil society and government organizations for AB 857. Member-chapters brought in countless volunteers, who worked through these committees to do on-the-ground outreach.

The organizing process to translate this vision into a bill and pass it into law only took about 8 months, from when the Coalition first convened. This is an unusually short timeline, as these efforts can often take years. Organizers think this speaks to the great need for Wall Street alternatives and the broadly shared sentiment that corporations are too powerful in our daily lives and have no business making money off public entities. Of course, what matters most now is that these banks adhere to the kind of progressive social and environmental criteria that will shape how they do business. It is up to local chapters organizing for their local public banks to ensure these banks have clear guidelines to support low-income communities and places facing legacies of disinvestment, gentrification, and environmental destruction. But the passing of this law has opened a huge opportunity for them to do just that.

What are the benefits and impacts of this policy?

The law went into effect in January 2020, yet it does not fully go into effect until the Department of Business Oversight issues regulations for these banks, which could be another six months. After that, any city or county can apply, so many municipalities are already working on business plans and applications. San Francisco, for instance, has convened a task force to start making the plan, with Los Angeles and groups in rural areas following close behind. In terms of impacts, at this early stage the Alliance can report a high level of excitement and interest around the creation of public banks, and especially a major increase in education and awareness that this people-powered option exists and is viable. Broadly, this awareness helps to shape the conversation around ways to strengthen the public sector around the state. We won’t see the true impacts of these banks individually until after they are established.

Anything else those working toward something similar should know?

People working toward public banks need to intentionally decide if they are trying to start a state-level bank or a city/county-level bank. For state-level banks, groups will need significant backing from the Governor of California. In California’s case, the Governor was already supportive and the California Public Banking Alliance did not request any money from him. New Jersey provides a different example: the initiative to create a state-level public bank is coming directly from the Governor. In that case, it might be easier for local activities to work through cities.

The scope and scale of the bank is also important. Another suggestion is to try to avoid the FDIC insurance requirement. That FDIC insurance mandate in California is a challenge for organizers because there is no precedent for the FDIC to insure a public bank. This means that in addition to members putting together a business plan for the bank (already a tough task), the Alliance is also working with state and federal regulators to discover how public banks will be granted FDIC insurance (it’s worth noting the Bank of North Dakota does not have FDIC insurance).

Additionally, deciding whether the public bank is intended for consumer banking or taxpayer deposits matters. Pushing for a public bank with consumer banking might create pushback from community banks and credit unions, which already offer those services to local clientele. The California Public Banking Alliance received pushback from big banks, and ultimately had support on the ground from credit unions and from a select few community banks. The support from credit unions came after time: At first, credit unions were explicitly opposed to the public banks, until the Alliance committed to not using the public banks for consumer banking. This support from community banks and credit unions isolated big banks as the Alliance’s opposition. Opposition also came from the State County Treasurers Association — the people who decide where a county’s public money is invested — and who had decided to invest in Wall Street banks up until this point.

“Both finding allies and being clear on who is your opposition and why, is important for these campaigns. Not everyone will be on your side, but knowing who is and isn’t can make or break the fight.”